House of Bondage

Ernest Cole

After 55 years out of print, House of Bondage was reissued in 2022 by Aperture. In this newly reissued photobook from 1967, Ernest Cole surveys the ever-present atrocities of apartheid: the regime of racial segretation in South Africa that lasted from 1948 to the early 1990s.

House of Bondage was authored by a self-taught black South African photojournalist, Ernest Cole (born 1940), and shows his experience of apartheid from the inside. Cole was born in Eersterust in Pretoria. His original family name was Kole and he later took the name Cole. Born in a township, Cole experienced the strains of apartheid first hand. As one of the first black freelance photographers, he offered an unprecedented view ‘from the inside’.

In 1966, Cole fled South Africa and smuggled out his negatives. House of Bondage was published the following year with his writings and first person account. It openly denounced the apartheid regime and was promptly banned in South Africa. At risk of arrest, Cole went into exile and never returned to South Africa.

After the publication of his book House of Bondage Cole lived a nomadic life. Living between Sweden and the US, Cole continued to document black lives. Being black and stateless proved debilitating. There was no publication of his American work. Towards the end of his life Cole became increasingly disillusioned and reportedly started living on the streets of New York. Cole died aged 49 from pancreatic cancer in 1990. Since then, 60.000 negatives kept in a safety deposit box in Sweden were discovered. The archive contains unpublished photographs and contact sheets from his original project House of Bondage.

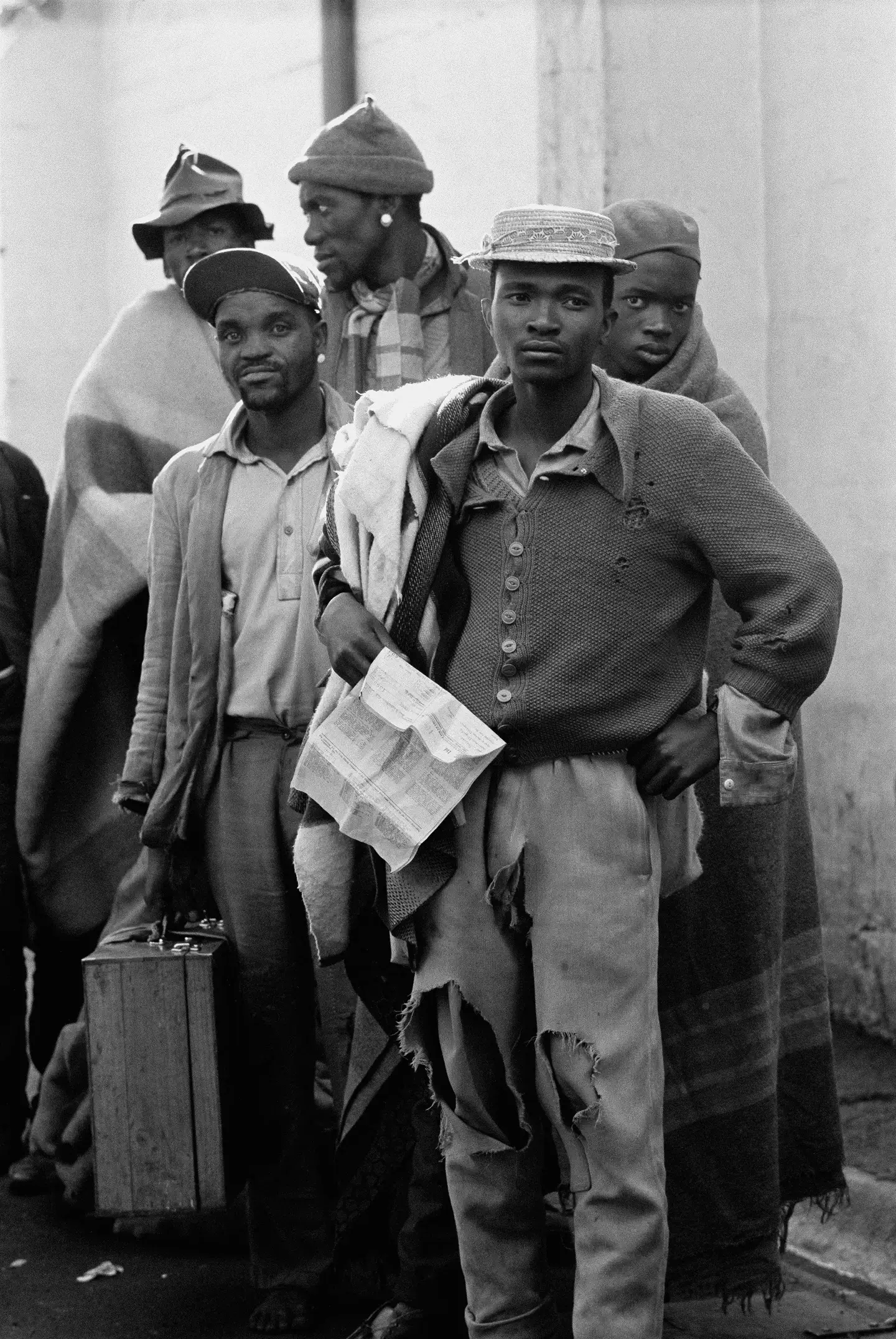

Cole spend much of the 1950s and ’60s determined to show the world what the white South African had done to the Black. Defying the pass police and hiding his camera in a paper bag, Cole surveyed crumbling schools, hospitals and workers’dwellings, the streets where discretionary arrests enforced a dailty climate of terror. House of Bondage also witnesses a people’s determination to continue living: socializing and studying, playing sports and music.

By fooling the authorities, Cole managed to get him officially reclassified as ‘coloured’ rather than ‘black’. Thereby raising himself half a notch up South Africa’s rigid social scale. And gaining himself more freedom of movement so he could access places where most black South Africans were banned. He then persuaded the Afrikaner Authorities that the story he was photographing was about street crime amongs disaffected ungrateful black youths rather than the appalling social inequalities of the apartheid system.

But the story behind the genesis of House of Bondage should not blind us to the fact that it is a work of genuine quality. It is a comprehensive view of black South African life under apartheid. Its text, written by Cole with the assistance of Thomas Flaherty, is integral to the pictures, making the book as much sociological document as photo-essay and polemic. Although the strictures of life in the black townships are heavily featured and there is crime and poverty aplenty, Cole also focused on education and work, and even on the aspiring black middle class. Nevertheless, as the title indicates, the story is mainly one of deprivation and the inevitable spiral of crime and violence that were its results. Some of the sequences – such as those on the tsotsis (street gangs) – are deeply memorable. Cole also documents the institutional violence of the apartheid policy – the passbook arrests, police inspections, dehumanizing conditionsin in the diamond mines and all the humiliating street signage that accompanied social segregation. The comprehensiveness and humanity of its view is the reason for both its banning in South Afrca and the plaudits it garnered elsewhere.

House of Bondage

Photographer: Ernest Cole

Originally published in 1967 by Random House

Reissued in 2022 by Aperture

Hardback, 21 x 29 cm, 232 pages, 227 images

Texts by Oluremi C. Onabanjo, James Sanders and Mongane Wally Serote

Mentioned in The Photobook: A History, Volume 2. Edited by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger