Antlitz der Zeit

August Sander

I am a big fan of August Sander’s photo portraits. Recently I bought a print of a photo he took: Jungbauern (Young Farmers). This photograph of three young farmers by August Sander is one of the highlights in the history of photography. The photo is synomynous with the photographer’s photoportraiture.

The picture documents the Sunday walk taken by the dapper men in rural Westerwald. It also brings home, as the picture is taken in 1914, the life of a generation growing up in the shadow of the impending World War I. It shows people whose plans for the future will soon be shattered. With their smart suits, modern hats, and walking canes the young men seem to be running to meet a new world. Uniformly dressed, the three men represent the modern men of their day. But the portrait lends itself also to the individual image. For as uniform as the three men may be conducting themselves, the expressions on their faces are very different.

August Sander (1876 – 1964) was a German portrait and documentary photographer. In the mid 1920s he began his decades-long project People of the Twentieth Century, a portrait study of the German people during the Weimar Republic. Only Edward S. Curtis’s American Indian study exceeded August Sander’s project in size.

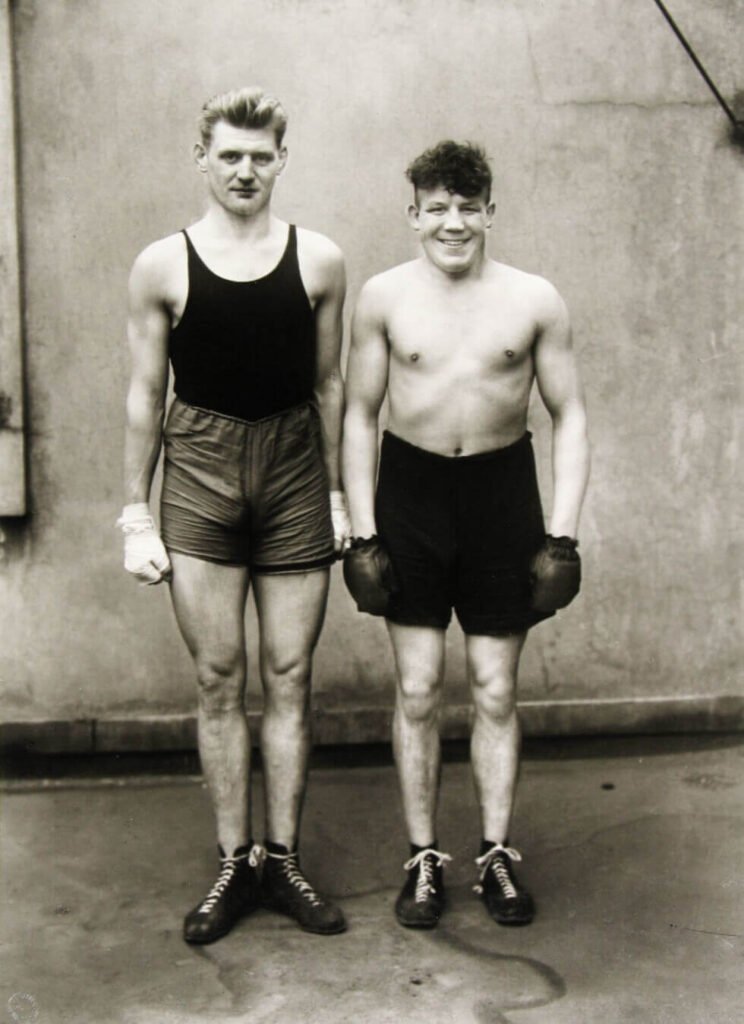

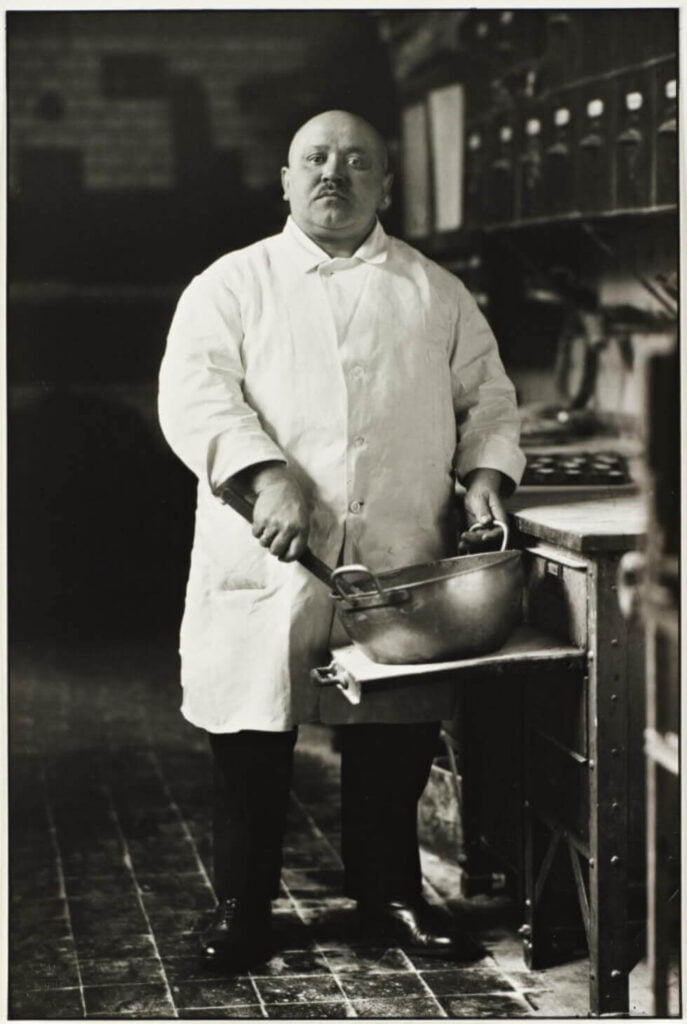

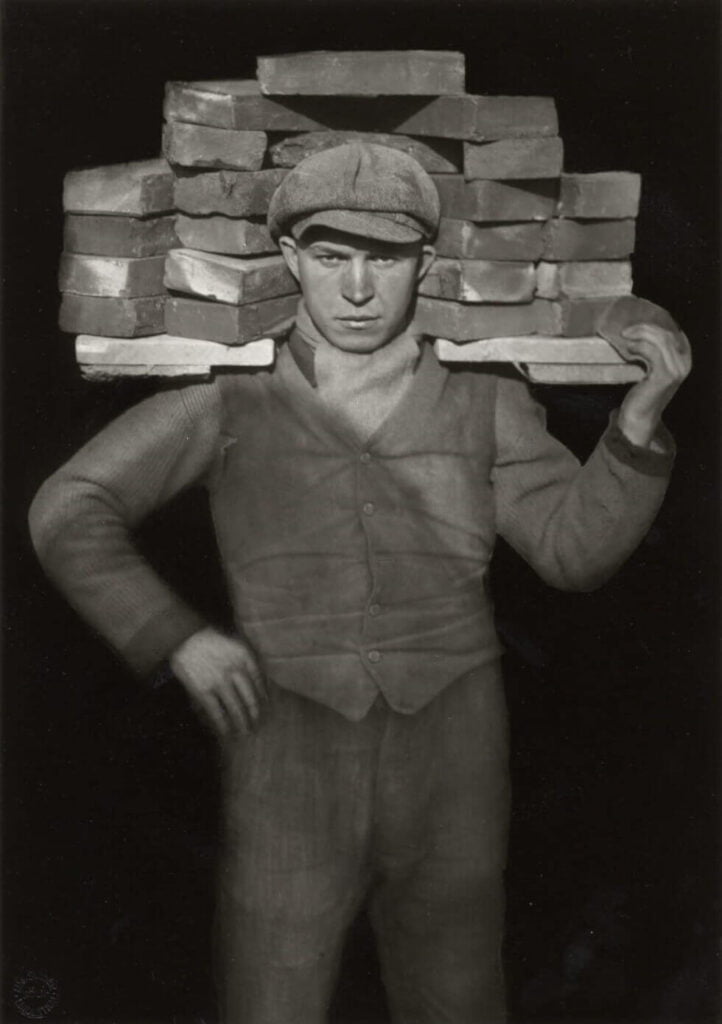

Sander never completed this exceptionally ambitious project. Nevertheless it includes 619 portraits of Germans from various social and economic backgrounds. The portraits often include familiar signifiers: a farmer with his scythe, a pastry cook in a bakery with a large mixing bowl. With his project he sought to create a mirror of society. His hundreds of different portraits were intended to gain knowledge by means of comparative vision.

One of the project’s contradictions is that each portrait the image is of an individual, and at the same time an image of a type. That’s because the project is rooted in the dubious nineteenth-century ‘science’ of physiognomy, the study of the systematic correspondence of psychological characteristics with facial features and body structure. Sander believed an individual face could speak for a whole generation.

Whatever its roots, Sander’s magnum opus was thoroughly of the twentieth century. As a practioner of New Objectivity (in German Neue Sachlichkeit), an avant-garde art movement, including Aenne Biermann, that sought to depart from abstraction and artifice and return to realism, Sander wanted his photographs to expose truths.

Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), published in 1929, was an interim report on the way to the ultimate multi-volume publication that Sander proposed. A selection of a mere 60 pictures out of hundreds, introduced by an essay by Alfred Döblin.. But many of his classic images are included in this seminal photobook, including the one of the young farmers. Although it is only a selection, the essential qualities of Sander’s vision are clear.

One of his work’s miracles is how, despite his nominal objectivity, his political view shines through. His work is not neutral. It is not just penetrating, but was seen as positively dangerous. A little too acute in its analysis of society and class,. This became clear when the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933. Publisher’s copies of Antlitz der Zeit were seized, the plates destroyed, and the negatives confiscated.

Sander’s work continues to be a source of inspiration for generations of photographers, including Walker Evans, Diane Arbus and Judith Joy Ross. He also changed the way many of us think about portraiture, informed the way we see gender and class, and shaped discussions around the archive as art and the idea of the documentary.

Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time)

Photographer: August Sander

Originally published in 1929 by the Kurt Wolff Verlag

144 pages, 60 duotone plates

Introduced by Alfred Döblin

Considered as one of the greatest photobooks of all time by Source Magazine.

Mentioned in The Photobook. A History Volume 1. Edited by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger.