American Photographs

Walker Evans

In 1938 an exhibition, Walker Evans: American Photographs, was held in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This was the first exhibition in the museum devoted to the work of a single photographer. The accompanying catalogue of the exhibition was published and is considered one of the greatest photobooks of all time.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1903, Walker Evans took up photography in 1928. In 1935 he got a position in the Resettlement Adminitration, later renamed as the Farm Security Administration (FSA). In the summer of 1936, while on leave from the FSA, he got an assignment from Fortune magazine. Together with writer James Agee he was sent to Hale County, Alabama to describe the lives of three tenant farmer families. It resulted in the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. It is considered a classic both literary as photographic. After the exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art in 1938 Evans resigned from the FSA. From 1945 to 1965 he was staff photographer and editor for Fortune magazine. Evans died in New Haven, Connecticut in 1975.

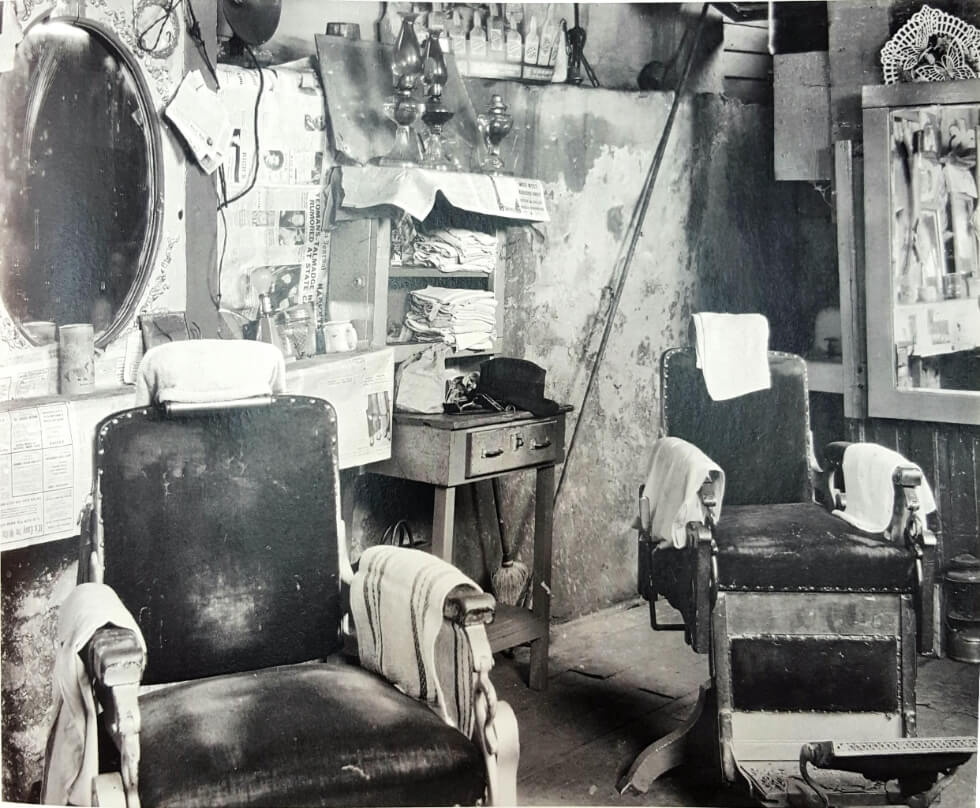

Evans turned his lens on everyday stuff that most other photographers chose to ignore. He turned those subjects into an enduring vision of Americanness: main streets lined with storefronts and Ford Model-Ts, roadside stands adorned with Coca Cola signs, the formulaic clapboard homes of factory workers. Evans was fascinated by a country searching for roots and a national identity. In the eyes of Evans the tenets of American culture were mass production, consumerism and the eventual obsolence of all things new.

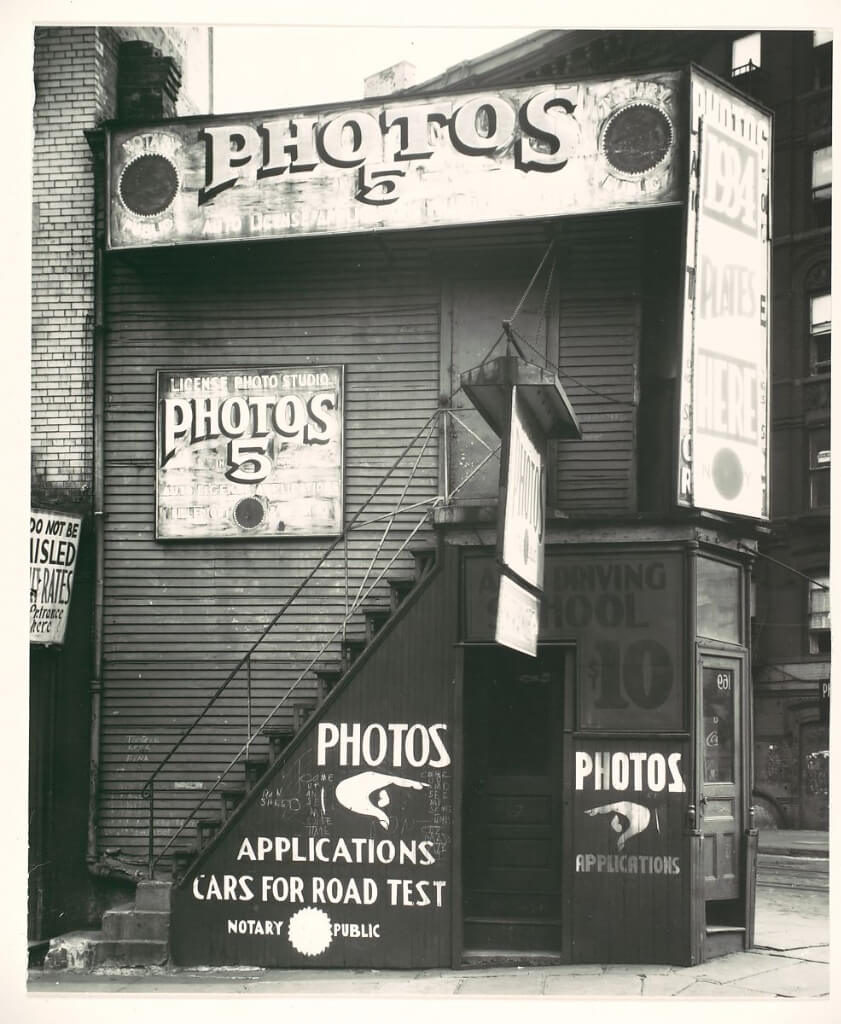

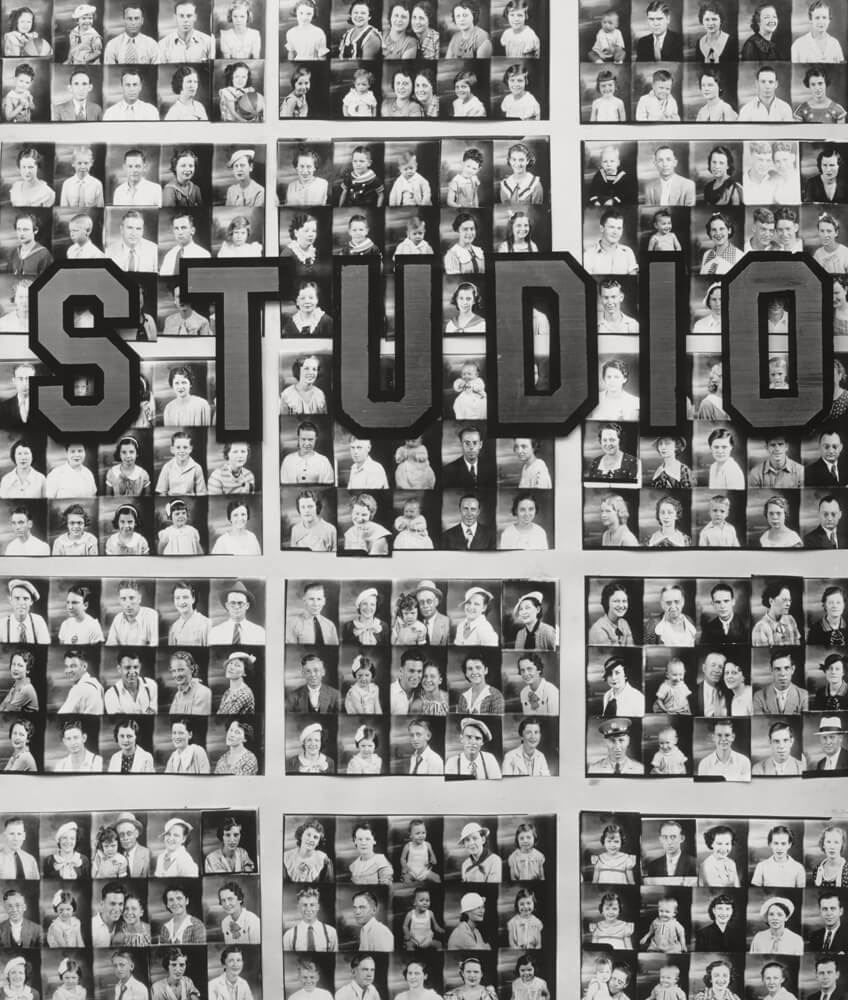

American Photographs states its theme from the outset. Its initial sequence begins with an image of a photographer’s shop, and includes a window display of penny snapshot photographs and a torn movie poster. Thus it declares itself not just a book about the world, but also about photography. How photography represents the world, and the tales that photographs can be made to tell.

Each individual picture is great. They are full of bitter irony and poignancy, piling up metaphors about the gap between intention and reality, about sight, about violence and poverty, about restricted lives behind mean facades, about indomitable hope of those little people who attempt to fashion, however crudely, their own piece of the American Dream. For instance there is a picture of a cactus obscuring the view of famiily photos and the American flag. I guess that illustrates well how Evans sees the American dream.

But what sets Evans apart from photographers before him, is the way he tells a story. Just like in films and literature he gives the book a clear but fluid narrative structure. A sense that it must be ‘read’ as well as looked at. How the pictures were laid out, as much so as the order of words in a sentence, gave the work its meaning.

American Photographs holds a well-deserved place at the top of the pantheon, and should be studied assiduously by any photographer attempting the tricky business of compiling a coherent photobook. However, it must be said that its second section is not as good as the first. In the second section the momentum that had been built up so well flags a little, as the book settles down to being merely an inventory of things, mainly buildings.

American Photographs remains a great work of art, for it showed us all just what might be accomplished by the photobook. It laid the groundwork for the whole artistic potential of what the photobook became in the 20th century.

American Photographs

Photographer: Walker Evans

Publisher: The Museum of Modern Art

Originally published in 1938

Hardcover, 20 x 23 cm, 208 pages, 87 illustrations

Essay by Lincoln Kirstein

Considered as one of the greatest photobooks of all time by Source Magazine

Mentioned in The Photobook: A History. Volume 1. Edited by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger.